DATE: 20030224

DOCKET: C37464

AUSTIN, ROSENBERG AND GILLESE JJ.A.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On appeal from the order of Justice Gordon P. Killeen of the Superior Court of Justice dated November 27, 2001.

ROSENBERG J.A.:

[1] This is an appeal from an order of Killeen J. staying an action concerning the affairs of CanWest Broadcasting Ltd. ("Broadcasting"). The motions judge held that the Ontario courts have no jurisdiction to try the action. He held, in the alternative, that Manitoba was the convenient forum for trial of the action. Finally, he set aside service of the statement of claim on the respondent Israel Asper. In my view, the motions judge erred in holding that the Ontario courts had no jurisdiction. However, I would not interfere with the motions judge's conclusion concerning convenient forum and, accordingly, I would dismiss the appeal with costs. In view of that conclusion, it is unnecessary to finally determine the question of service upon Mr. Asper.

[2] The appellants applied to introduce fresh evidence at the hearing of the appeal. The respondents opposed the admission of this evidence. In accordance with its usual practice, the court reserved judgment on the admission of the fresh evidence. On December 11, 2002, counsel for the respondents wrote to the court to provide additional information concerning the proposed fresh evidence. The respondents wish this court to consider this new information, should it admit the fresh evidence. For the reasons that follow, I would not admit the fresh evidence.

THE FACTS

Introduction

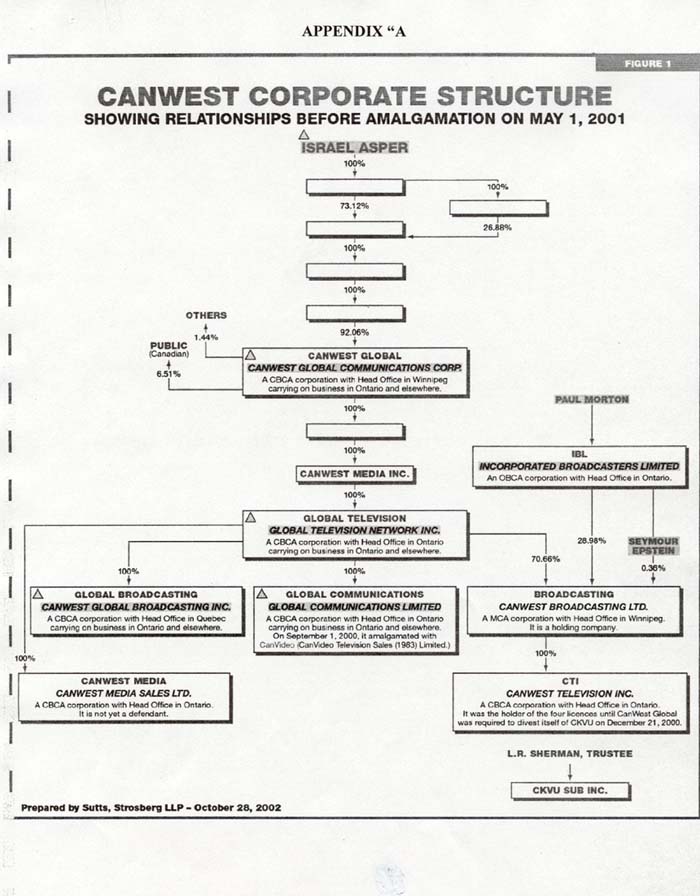

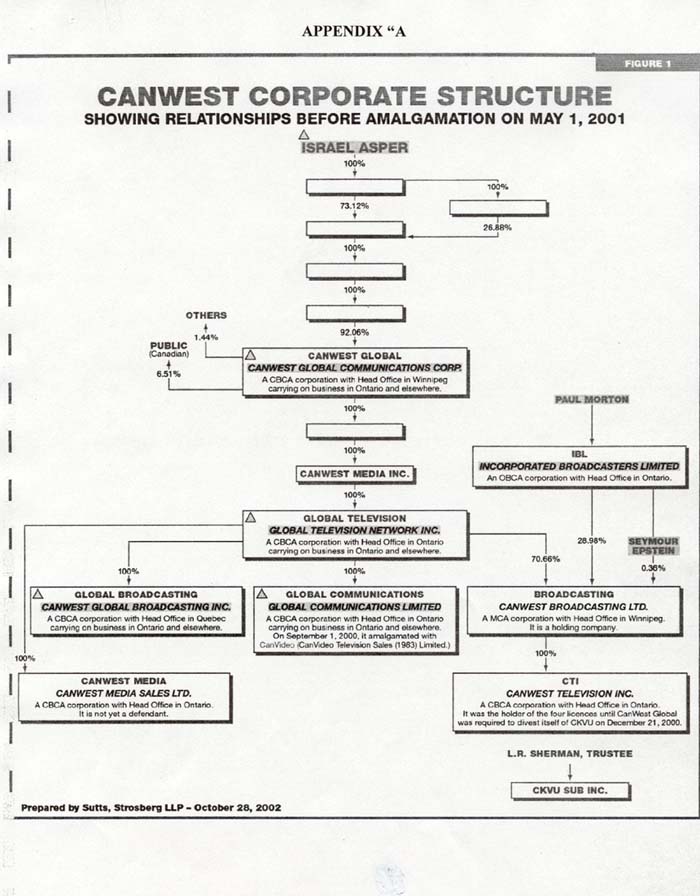

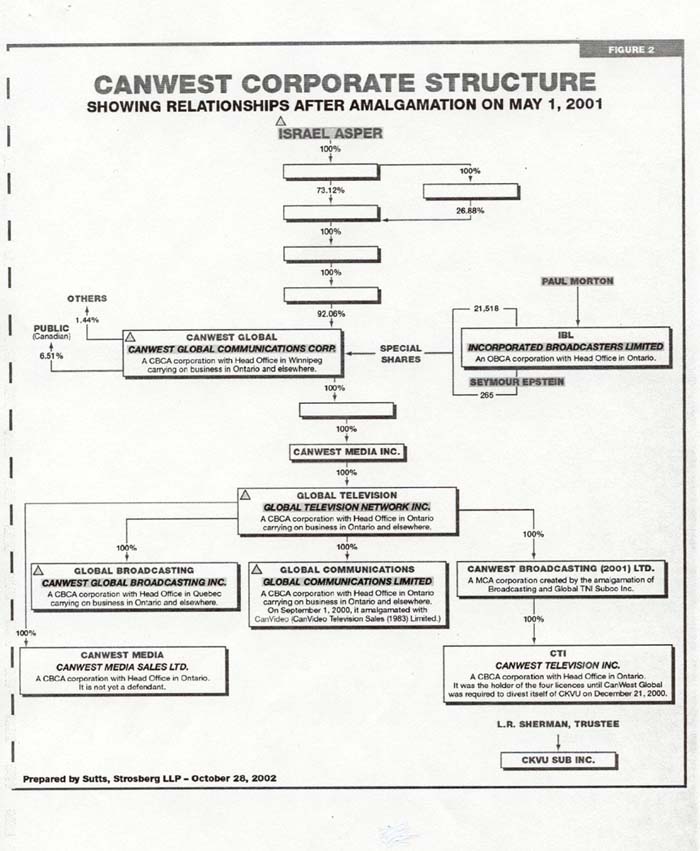

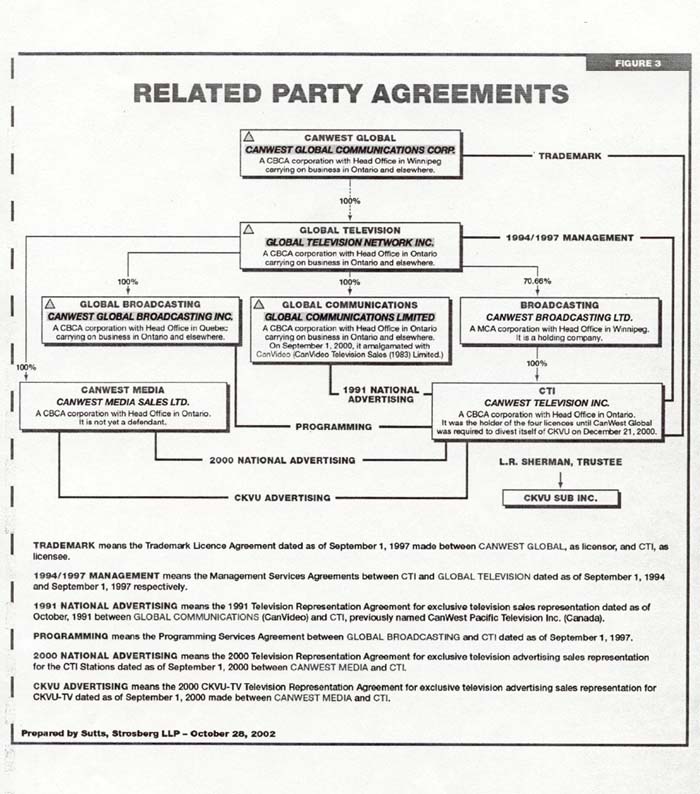

[3] The relationships among the various parties to this lawsuit dates back to 1973 when Mr. Asper led the efforts to establish Broadcasting, a Manitoba corporation designed to operate an independent television station in Winnipeg called CKND. The background facts concerning this relationship are set out in the reasons of Morse J. in Morton v. Asper (1989), 62 Man. R. (2d) 1 (Q.B.) when he dealt with earlier litigation between many of these same parties and in the reasons of Killeen J., which are reported at (2001), 20 B.L.R. (3d) 289 (Ont. S.C.J.). I intend to give only a very brief summary of those earlier facts since the case for or against the Ontario courts assuming jurisdiction in this case must be found in the appellants' statement of claim and the evidence presented on the motion. The corporate structure of the various parties is somewhat complex. I have therefore attached as Appendix "A" three charts prepared by the appellants.

The Background Facts

[4] In 1973, the individual parties, the respondent Asper, and the appellants Morton and Epstein, along with two others, became the founding shareholders of Broadcasting. In 1974, Broadcasting obtained its television licence from the Canadian Radio and Television Commission and CKND went on the air. As mentioned, Broadcasting is a Manitoba corporation.

[5] Around the same time that Broadcasting was becoming established, Global Television Network Inc. ("Global Television")was running into financial difficulties and Mr. Epstein, who resides in Ontario, convinced Mr. Asper and Mr. Morton, who resided in Winnipeg, to invest in Global Television. The Winnipeg group invested in Global Television through Global Ventures Western Limited ("Ventures"). Mr. Epstein also invested, as did another company. In 1977, this other company triggered a buy-sell agreement that resulted in Ventures owning a majority of the voting shares of Global Television. After several transactions, Ventures ended up with control of 100% of Global Television shares. The individual parties held their stakes in Global Television through Ventures. Mr. Morton moved to Toronto and became president of Global Television. A Unanimous Shareholders Agreement governed the relationship between the parties. This agreement was governed by the laws of Manitoba. During this period, Morton and Epstein focused most of their attention on Global Television.

[6] By the mid-1980's, there was growing friction between Asper and the Ontario parties Epstein and Morton that led to the Manitoba litigation presided over by Morse J. This litigation was initiated by Morton and Epstein in Manitoba and sought to implement the terms of a 1985 agreement. Morse J. concluded that the two groups of shareholders were hopelessly deadlocked over the affairs of Ventures and Global Television. He therefore directed an auction that resulted in Morton and Epstein and their companies selling their interest in Global Television to CanWest Global Communications Corp. ("CanWest Global"), a company controlled by Mr. Asper. While this took Mr. Morton and Mr. Epstein out of Ventures and Global Television, they remained shareholders in Broadcasting.

Broadcasting

[7] While Mr. Morton and Mr. Epstein had been engaged in Global Television, Broadcasting had continued to expand. It continued to operate its Manitoba television station (CKND) and it acquired three other stations in Western Canada including CKVU in Vancouver. Broadcasting did not operate any stations in Ontario. Broadcasting's lands and buildings are owned by its wholly owned subsidiary, CanWest Properties Ltd., a Manitoba corporation. Broadcasting's television licences are held by CanWest Television Inc. (CTI), a federal corporation and wholly owned subsidiary of Broadcasting.

[8] Once divested of their direct connection with Global Television as a result of the 1989 auction, Mr. Morton and Mr. Epstein now took a greater interest in Broadcasting. Through their company, the appellant Incorporated Broadcasters Limited (IBL), Mr. Morton and Mr. Epstein held 28.96% of the shares of Broadcasting. IBL is an Ontario corporation with its registered office in Toronto. As well, Mr. Epstein personally held .36% of the shares of Broadcasting. Mr. Morton and Mr. Epstein were directors of Broadcasting and CTI. The balance of Broadcasting shares were held by Global Television, a federally incorporated corporation with its registered office in Ontario[1]. Global Television is, in effect, a wholly owned subsidiary of CanWest Global, a federally incorporated corporation with its registered office in Winnipeg, which is in turn controlled by Mr. Asper.

[9] Since the 1989 auction, Mr. Morton and Mr. Epstein have voiced concerns about the operations of Broadcasting. Among other things they allege that Asper has used his position as majority shareholder to favour his corporations, to squeeze Morton and Epstein out of Broadcasting's operations and reduce their management fees. The appellant MAE Management Corporation, an Ontario corporation with its registered office in Toronto was the vehicle used by Epstein and Morton to collect their management fees for services provided to Global Television and Broadcasting. I will outline the appellants' concerns in greater detail below when I review the allegations in the statement of claim.

[10] One of the proposals made by Mr. Asper for alleviating the friction was to have Mr. Morton and Mr. Epstein sell their holdings in Broadcasting and become shareholders of CanWest Global. In that way, they too would benefit from the way that CanWest Global exercised its control over Broadcasting. Mr. Morton and Mr. Epstein took some steps in that direction and in December 1996 prepared an offer to sell their shares in Broadcasting. Nothing came of this offer, but the friction continued. In January 2000, Broadcasting was considering a merger or amalgamation with a subsidiary of CanWest Global.

The Lawsuit

[11] On March 5, 2001, the appellants launched their lawsuit. The plaintiffs are IBL, Morton, Epstein and MAE. The defendants are Asper, CanWest Global, Global Television and the two wholly owned subsidiaries of Global Television - CanWest Global-Broadcasting Inc. and Global Communications Limited - which as indicated, are both federal corporations.

[12] On March 15, 2001, CanWest Global advised the members of Broadcasting's Board of an amalgamation proposal. This amalgamation was effected on May 1, 2001 and a new Manitoba corporation, CanWest Broadcasting (2001) Ltd., was created. It is 100% owned by Global Television. CTI, formerly a wholly owned subsidiary of Broadcasting, is now a wholly owned subsidiary of CanWest (2001).

[13] As a result of the amalgamation, the CRTC required Broadcasting to divest itself of its Vancouver station, CKVU, because Global Television already owned a Vancouver station. Pending the sale, a trustee controlled CKVU. IBL and Mr. Epstein were issued special shares in CanWest Global. Mr. Morton and Mr. Epstein voted against the amalgamation but did not exercise the right of dissent to the amalgamation provided for in the Manitoba Corporations Act, R.S.M. 1987, c. C-225.

[14] Following the amalgamation, the appellants amended their statement of claim. In the amended statement of claim, the appellants seek declarations, an accounting, damages and other relief. The appellants seek a declaration that:

[15] The appellants also seek an accounting of the profits from these actions and damages of $355 million from CanWest Global for breach of contracts made with CanWest Global for management services provided to Broadcasting and its subsidiaries and for diversion of certain of Broadcasting's profits. IBL and Epstein also seek an order requiring CanWest Global to direct Broadcasting to declare and pay dividends to its shareholders and an order requiring CanWest Global to purchase the shares of IBL and Epstein in Broadcasting.

[16] The appellants allege that CanWest Global has not adhered to the fiduciary standards of conduct owed to Mr. Epstein and Mr. Morton, and has managed the affairs of Broadcasting and its subsidiaries in a manner that is oppressive or is unfairly prejudicial to or unfairly disregards the interests of Mr. Epstein and IBL as security holders, directors and officers of Broadcasting. The conduct complained of includes the following:

(a) failing or refusing to pay dividends to Broadcasting's shareholders;

(b) removing Epstein and Morton from management of Broadcasting and replacing them with CanWest Global or Global Television management;

(c) removing any independent station identification from Broadcasting's televisions stations and replacing it with identification as a member of the Global Television Network;

(d) diverting profits from Broadcasting through numerous non-arm's length contracts with CanWest Global and its affiliates so that Broadcasting and its subsidiaries pay excessive fees;

(e) pursuing corporate opportunities through CanWest Global and its affiliates rather than through Broadcasting or its subsidiaries;

(f) compelling Broadcasting's stations to acquire programming at excessive rates through Global Television;

(g) purchasing through CanWest Global the Western International Communications Ltd. [WIC] television stations in Vancouver and elsewhere that are in direct competition with Broadcasting's Vancouver station CKVU-TV;

(h) breaching the duty of good faith performance of contractual and other duties owed to Broadcasting and its minority shareholders; and

(i) placing Broadcasting in the position where it was compelled to sell CKVU-TV in circumstances where CanWest Global has reduced the ability of CKVU-TV to compete with CanWest Global's newly-acquired stations.

[17] After setting out this overview of the complaints, the appellants (in almost 150 paragraphs) set out in detail the factual basis for these allegations. These allegations are founded on the conduct of Broadcasting's affairs culminating in the amalgamation. A few examples will suffice. I have set out in Appendix "B" other parts of the amended statement of claim that show the various courses of action.

44. Notwithstanding the 1982 management agreement and their partnership in respect of the business or affairs of Broadcasting, Asper has not permitted Epstein and Morton to provide any management services to Broadcasting. Since 1990, Epstein and Morton have not received, directly or indirectly, any distribution of a share of the profits of Broadcasting in the form of management fees from Broadcasting since the unilateral termination by Asper and/or CanWest Global of the 1982 management agreement

…

68. CanWest Global imposed unilaterally the change in allocating programming costs to Broadcasting and its subsidiaries in breach of the fiduciary obligations owed by CanWest Global to them and in breach of the express or implied term of the management agreements by CanWest Global and/or any of its subsidiaries to act in the best interests of Broadcasting and its subsidiaries.

…

81. The proposed financial arrangement was patently unfair to Broadcasting. As an example of the unfairness of the proposed formula, unlike the Global Television stations in Ontario whose signals reached virtually all of the English speaking population of that province, the Broadcasting station CKVU-TV (Vancouver) reached only a portion of the English speaking population of British Columbia. Further, the WIC station in Edmonton, Alberta provided its signal to a significant English speaking population in the interior of British Columbia. Accordingly, the proposed formula was based upon statistics that were unrelated to the number of people who actually received the signals of the Global Television and Broadcasting stations affected by the formula.

…

106. Through these non-arm's length transactions, CanWest Global has systematically withdrawn funds from Broadcasting. During the same period, CanWest Global has refused to pay any dividends to its minority shareholders, to pay management fees to them or provide any other form of compensation to or for the benefit of the minority shareholders.

107. In purpose and effect, CanWest Global has used these related party transactions to withdraw compensation from Broadcasting in a manner that is oppressive and unfairly prejudicial to or that unfairly disregards the interests of Broadcasting's minority shareholders.

…

123. Despite the fact that Broadcasting had the strategic position in the marketplace and, particularly in 1996, that Broadcasting had the available funding to exploit these important business opportunities, Asper, CanWest Global and Global Television directed their nominees on Broadcasting's board of directors to cause Broadcasting not to pursue these opportunities. They instructed the nominees instead to permit Global Television to apply for these Alberta licences without their intervention or opposition. In this way, Asper, CanWest Global and Global Television breached their fiduciary duties to Broadcasting, IBL, Epstein and Morton.

…

145. The purpose and the effect of the refusal by Asper, CanWest Global and Global Television to pay dividends to Broadcasting's shareholders have been to oppress, unfairly prejudice and unfairly disregard the interests of Broadcasting's minority shareholders. Coupled with CanWest Global's systematic withdrawal of funds from Broadcasting through the complex series of non-arm's length, related party management, programming, sales and other contracts, the net effect of Broadcasting's refusal to pay dividends is to divert a significant portion of Broadcasting's corporate profits to or for the benefit of CanWest Global.

…

160. Broadcasting is a closely-held corporation. IBL and Epstein are the only minority shareholders of Broadcasting whose rights were to be affected by the proposed amalgamation. Moreover, Broadcasting did not benefit from the amalgamation.

…

184. The refusal to declare dividends, the instructions given by Asper and CanWest Global and the amalgamation were high-handed, outrageous, mean-spirited, malevolent, oppressive, contumelious and unfairly prejudicial to and unfairly disregarded the interests of IBL and Epstein. In failing to cause the dividends to be paid and in orchestrating the amalgamation, Asper breached his fiduciary duty to Morton and Epstein and their company IBL.

[emphasis added].

THE PROPOSED FRESH EVIDENCE

[18] As a result of the amalgamation, the appellants received special shares in CanWest Global. The evidence before the motions judge was that those special shares would be redeemed by October 31, 2002, one year following the closing of the sale of CKVU to CHUM Limited. The appellants' proposed fresh evidence was that CanWest Global had not redeemed the special shares by the time of the hearing of the appeal on November 7, 2002. The further evidence filed by the respondents, following the argument of this appeal, is that on December 10, 2002, the Directors of CanWest Global resolved to redeem the appellants' special shares. This redemption was deemed to have taken place on December 18, 2002 with deposits into separate accounts established for IBL and for Mr. Epstein. IBL has tendered its shares and received the money. As of December 19, 2002, Mr. Epstein has not yet tendered his shares and so the money remained in the special account. As I have indicated, the respondents wish the court to consider this additional information, should it admit the appellant's fresh evidence.

THE REASONS OF THE MOTIONS JUDGE

Jurisdiction

[19] The motions judge held that Ontario courts could only have jurisdiction to hear the claims if there is a real and substantial connection between the subject matter of the claims and Ontario. He held that there is no such connection. His principal reason for that conclusion was that the claims are in the nature of an oppression action in respect of the affairs of Broadcasting, a Manitoba corporation. The various decisions about which the appellants complain concern decisions that were for the most part made in Manitoba by Broadcasting's board of directors.

[20] The motions judge rejected the appellants' position that Ontario courts had jurisdiction under s. 241 of the CBCA to grant an oppression remedy even though CanWest Global and Global Television are federal corporations, the latter having its registered office in Ontario. He held that although s. 241 allows a complainant to apply to a "court", which is defined as any provincial superior court, s. 241 does not itself confer subject-matter jurisdiction.

[21] The motions judge also held that the oppression remedy under s. 241 of the CBCA was not available to the appellants. He held that the complainant asserting the claim must be a shareholder of a CBCA corporation or the activities complained of must be in respect of the business and affairs of a CBCA corporation. That was not the case in respect of most of the claims since "at any relevant time" the appellants were only shareholders of Broadcasting, a Manitoba corporation.

[22] In addition to Manitoba having "the closest and most natural connection to the conduct complained of and the expectation of the parties that their disputes would be governed by Manitoba law", the motions judge held that only the Manitoba Court of Queen's Bench had jurisdiction, under the Manitoba Corporations Act, to deal with the appellants' claims of oppression. He held that while there were "points of connection" between Ontario and the appellants' action because of CanWest Global's and Global Television's activities in Ontario, they were "peripheral and tangential to the real substance of the dispute".

[23] The motions judge also saw this lawsuit as very much an extension of the earlier Manitoba litigation that had ended in the 1989 auction whereby Asper gained control of Global Television.

[24] Since the action had no real and substantial connection with Ontario and the CBCA did not confer jurisdiction, the Ontario courts had no jurisdiction and the action should be stayed.

Convenient Forum

[25] Alternatively, the motions judge held that Ontario is not the convenient forum for the trial of this case. He set out the various factors courts have looked to in determining convenient forum and applied the facts to those factors. An important factor, as in his consideration of jurisdiction, was that the subject matter of the dispute concerned the conduct of a Manitoba corporation. Another important factor was that the conduct complained of took place in Manitoba or in the western provinces where Broadcasting had its various television stations. The motions judge also looked at the status of the various corporations involved and where most of the evidence and the witnesses were situated. He therefore concluded that the respondents had shown that Manitoba was clearly the convenient forum.

Service ex juris

[26] Mr. Asper sought to set aside service of the statement of claim and amended statement of claim on the basis that the claims did not come within rule 17.02 of the Rules of Civil Procedure and Ontario was not a convenient forum. Rule 17.02 provides that a party may, without a court order, be served outside Ontario if the claim falls within certain categories. The motions judge held that the oppression claim asserted by the appellants does not fall within any of those categories. He also held that Asper was not a resident of Ontario in any meaningful sense. Further, Ontario was clearly not the convenient forum. He therefore set aside service of the statement of claim.

ANALYSIS

Fresh Evidence

[27] As I have indicated, the proposed fresh evidence concerns events following the amalgamation and the appellants' allegation that CanWest Global did not redeem the special shares on October 31, 2002, contrary to the representations that had been made to the motions judge. In my view, this issue played no part in the reasoning of the motions judge and I do not see its relevance to the issues on the appeal. For similar reasons, I would not admit the fresh evidence tendered by the respondents that CanWest Global has in fact now taken steps to redeem the shares. Even if, as a result, the appellants Epstein and IBL are no longer shareholders of any CBCA corporation and Morton is no longer a beneficial owner of shares, they would still have standing as complainants to seek an oppression remedy under s. 241, since s. 238 of the Act defines "complainant" to include a former director, officer, registered holder or beneficial owner of securities of a CBCA corporation or any of its affiliates.

[28] I would therefore dismiss the application to admit fresh evidence.

Jurisdiction

[29] In my view, the motions judge erred in applying the real and substantial connection test to determine jurisdiction in this case, except jurisdiction over Mr. Asper. The real and substantial connection test applies where a court seeks to assume jurisdiction over defendants that have no presence in the jurisdiction. The real and substantial connection test serves to extend jurisdiction of the domestic courts over out-of-province defendants. It is not a pre-requisite for the assertion of jurisdiction over defendants, even out-of-province defendants, that may be present in the jurisdiction. That test is concerned with what Sharpe J.A. referred to in Muscutt v. Courcelles (2002), 213 D.L.R. (4th) 577 (Ont. C.A.) as "assumed jurisdiction" not "presence-based jurisdiction". In Muscutt, Sharpe J.A. speaking for the court at para. 19 explained that there are "three ways in which jurisdiction may be asserted against an out-of-province defendant: (1) presence-based jurisdiction; (2) consent-based jurisdiction; and (3) assumed jurisdiction. Presence-based jurisdiction permits jurisdiction over an extra-provincial defendant who is physically present within the territory of the court."

[30] Earlier decisions of the Supreme Court concerning jurisdiction also indicate that the real and substantial connection test is limited to cases where the courts seek to assert jurisdiction over out-of-province defendants. In Morguard Investments Ltd. v. De Savoye, [1990] 3 S.C.R. 1077 the court considered when a court in one province should recognize the judgment of another province. The court held that provinces should recognize each other's judgments when it was appropriate for the court that gave the judgment to have assumed jurisdiction. At pages 1103-4 La Forest J. explained the traditional limits of jurisdiction. As he said, the question of appropriate jurisdiction "poses no difficulty where the court has acted on the basis of some ground traditionally accepted by courts as permitting the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments - in the case of judgments in personam where the defendant was within the jurisdiction at the time of the action or when he submitted to its judgment whether by agreement or attornment". Where the defendant is within the jurisdiction, the court has jurisdiction over the person. The difficulty arises where the defendant is outside the jurisdiction of the court. The question then is to what extent a court of one province may properly exercise jurisdiction over a defendant in another province?" In Morguard, La Forest J. answered that question by adopting the real and substantial test for assuming jurisdiction over extra-provincial defendants.

[31] As I will explain below, the only person who may not have a presence in Ontario for the purposes of jurisdiction is Mr. Asper. It is only with respect to him that the real and substantial connection test applies. But, as I will explain, the test is easily satisfied in this case. Before turning to that part of the analysis I need to deal with one argument made by the respondents.

[32] The respondents contend that irrespective of whether the defendant is present in the jurisdiction, as a matter of constitutional law, there must be a real and substantial connection between the subject matter of the litigation and the province. In Morguard, La Forest J. held at p. 1109 that, "[t]he private international law rule requiring substantial connection with the jurisdiction where the action took place is supported by the constitutional restriction of legislative power 'in the province'." At p. 1109, he quoted with approval a comment by Professor Hogg on the earlier decision in Moran v. Pyle National (Canada) Ltd., [1975] 1 S.C.R. 393, which strongly suggests that the constitutional issue is relevant only where the courts seeks to assert jurisdiction over out-of-province defendants:

In Moran v. Pyle, Dickson J. emphasized that the "sole issue" was whether Saskatchewan's rules regarding jurisdiction based on service ex juris had been complied with. He did not consider whether there were constitutional limits on the jurisdiction which could be conferred by the Saskatchewan Legislature on the Saskatchewan courts. But the rule which he announced could serve satisfactorily as a statement of the constitutional limits of provincial-court jurisdiction over defendants outside the province, requiring as it does a substantial connection between the defendant and the forum province of a kind which makes it reasonable to infer that the defendant has voluntarily submitted himself to the risk of litigation in the courts of the forum province" [emphasis added].

[33] There is no constitutional impediment to a court asserting jurisdiction over a person having a presence in the province.

[34] The respondents also relied on the following passage from Professor Castel's treatise, Canadian Conflict of Laws, 4th ed. (Toronto: Butterworths, 1997), at p. 54:

In Hunt v. T. & N. plc, the Supreme Court of Canada gave constitutional status to the principles expounded in Morguard. Therefore, the requirement of "a real and substantial connection" has become the absolute constitutional limit on the power of each province to confer judicial jurisdiction on its courts. Whenever a defendant is served in juris or ex juris with the process of a court of a Canadian province, he or she may challenge the proceeding on constitutional grounds if the forum province lacks a real and substantial connection with the subject matter of the proceeding or the defendant. The requirement of a real and substantial connection places a limit on the provincial rules of procedure since the provincial power to legislate with respect to service in juris or ex juris requires some serious contacts with the province [emphasis added].

[35] But, it seems to me that in the part of the passage that I have emphasized, Professor Castel was careful to distinguish between defendants in the province and extra-provincial defendants since he refers to a need for a connection to the subject matter of the proceeding "or the defendant". Further, earlier in his text at p. 53, Professor Castel indicates that the discussion concerns the "constitutional limits to the exercise of jurisdiction against persons outside the province".

[36] As I have said, it is my view that, with the exception of Mr. Asper, all of the defendants have a presence in Ontario that makes them subject to the jurisdiction of the Ontario courts. CanWest Global is a federally incorporated corporation with its registered office in Winnipeg. However, it carries on business in Ontario in television, newspapers, and radio, specialty cable channels and Internet websites. By choosing to carry on business in Ontario, CanWest Global is subject to the jurisdiction of Ontario courts. See Hunt v. T&N PLC, [1993] 4 S.C.R. 289 at 323. The defendants Global Television and Global Communications Limited are federally incorporated corporations with registered offices in Ontario carrying on business in Ontario. By virtue of their place of registered office and where they carry on business they are resident in Ontario and therefore subject to the jurisdiction of the Ontario courts. See K.P. McGuinness, The Law and Practice of Canadian Business Corporations (Toronto: Butterworths, 1999) at pp. 266-69. The defendant CanVideo Television Sales (1983) Limited was originally an Ontario corporation and is now a federally incorporated corporation and carries on business from offices in Toronto and is subject to the jurisdiction of the Ontario courts. The defendant CanWest Global Broadcasting Inc. is a federal corporation with its registered office in Quebec but with offices in Toronto. It too is subject to the jurisdiction of Ontario courts.

[37] This leaves only Mr. Asper. Mr. Asper resides in Manitoba. For the purposes of this discussion I will assume that he was properly served in Ontario. Whether served in or out of Ontario, since he is an extra-provincial defendant, Ontario courts only have jurisdiction over him if the real and substantial connection test is met.

[38] I would make two preliminary comments about the application of that test. First, "the real and substantial connection test requires only a real and substantial connection, not the most real and substantial connection" (Muscutt at para. 44). Second, in my view, the dominant consideration in applying that test is that the other defendants are present in Ontario and, subject to the convenient forum argument, their trial will take place here. Goudge J.A. discussed the proper approach in such a case in McNichol Estate v. Woldnik (2001), 13 C.P.C. (5th) 61 (Ont. C.A.) at para. 13 where he explained that if it serves the requirements of order and fairness to try the foreign claim together with the claims that are clearly rooted in Ontario, the foreign claim meets the real and substantial connection test. This is so even if the foreign claim would fail the test if it were constituted as a separate action. Goudge J.A. states: "[t]his approach goes beyond showing that the foreign defendant is a proper party to the litigation. It rests on those values, namely order and fairness, that properly inform the real and substantial connection test and allows the court the flexibility to balance the globalization of litigation against the problems for a defendant who is sued in a foreign jurisdiction" [at para. 13]. Mr. Asper is the operating mind behind the various CanWest and Global corporations. It would make little sense to try the claims against him separately.

[39] With that background I will now apply the real and substantial connection test to Mr. Asper. In Muscutt, Sharpe J.A. set out a number of factors for the courts to consider in applying the real and substantial connection test. I will briefly discuss each of them as they apply to Mr. Asper:

(1) The connection between the forum and the plaintiff's claim.

[40] As Sharpe J.A. points out at para. 77, "[t]he forum has an interest in protecting the legal rights of its residents and affording injured plaintiffs generous access for litigating claims against tortfeasors". This is not a tort claim but similar considerations apply. The appellants are all residents of Ontario and claim to have been injured by the conduct of the various defendants. They rely upon the statutory cause of action in s. 241 of the CBCA that gives a complainant access to the courts for a remedy against oppressive conduct by a CBCA corporation or its affiliates. Section 2 of that Act defines "court" to include the Superior Court of Justice in Ontario.

(2) The connection between the forum and the defendant.

[41] At para. 82 of Muscutt, Sharpe J.A. held that if the defendant "has done anything within the jurisdiction that bears upon the claim advanced by the plaintiff, the case for assuming jurisdiction is strengthened". Mr. Asper carries on business through various corporations, many of which carry on business in Ontario. The trial judge found that he comes to Ontario six times a year for business purposes. The Broadcasting board of directors has met in Ontario in the past. Asper thus has some connection with Ontario as it bears upon the appellants' claim.

(3) Unfairness to the defendant in assuming jurisdiction.

[42] It is not apparent that there would be any unfairness to Asper if the Ontario courts were to assume jurisdiction. He is engaged in an activity with Canada-wide connections. It cannot be totally unexpected that he might find himself in an Ontario court because of those activities.

(4) Unfairness to the plaintiff in not assuming jurisdiction.

[43] If jurisdiction were refused, the appellants would be required to litigate in Manitoba. Given that Broadcasting is a Manitoba corporation and that they have litigated in Manitoba before, there is no apparent unfairness in refusing to assume jurisdiction.

(5) The involvement of other parties to the suit.

[44] I have already discussed this factor above. As indicated, it is a very important consideration favouring a finding of a real and substantial connection in this case.

(6) The court's willingness to recognize and enforce an extraprovincial judgment rendered on the same jurisdictional basis.

[45] The appellants seek a remedy under the CBCA, a federal statute, for oppression allegedly caused by federal corporations and their affiliates at the direction of Mr. Asper. I think it appropriate that Ontario courts recognize and enforce judgments from the other provinces rendered on the same jurisdictional basis as in this case. [2]

(7) Whether the case is interprovincial or international in nature.

[46] As Sharpe J.A. pointed out in Muscutt, at para. 95, "the assumption of jurisdiction is more easily justified in interprovincial cases than in international cases". Since this is an interprovincial case, this factor also favours the finding of a real and substantial connection.

(8) Comity and the standards of jurisdiction, recognition and enforcement prevailing elsewhere.

[47] As this is an interprovincial case, this factor has no application: Muscutt at para. 102.

Conclusion on real and substantial connection as applied to Mr. Asper

[48] As held in Muscutt, no single factor is determinative. Rather, "all relevant factors should be considered and weighed together" (at para. 76). In my view, the various factors, but particularly the involvement of other parties to the lawsuit and his business connections to Ontario, favour assuming jurisdiction over Mr. Asper, the extraprovincial defendant.

Convenient Forum

[49] As it was put by Arbour J.A. in Frymer v. Brettschneider (1994), 19 O.R. (3d) 60 (C.A.) at 79, when an issue of convenient forum is raised, the "choice of the appropriate forum is designed to ensure that the action is tried in the jurisdiction that has the closest connection with the action and the parties". In this case, the appellants have chosen Ontario. The new corporation Broadcasting (2001) and the respondent CanWest Global have brought an application in the Manitoba Court of Queen's Bench for declarations to determine the rights of the appellants to any relief in respect of the conduct of the affairs of Broadcasting. That application has been held in abeyance pending this appeal.

[50] Before I apply the various factors identified in the cases for determining convenient forum, I think it is necessary to characterize the nature of the appellants' lawsuit. The motions judge characterized the lawsuit as "an oppression action relating to the affairs of Broadcasting". He elaborated on that theme, for example, as follows:

The real source of the alleged oppression must, if anywhere, be within the conduct of affairs in Broadcasting. The allegations of oppression are inescapably "in respect of" Broadcasting [at para. 76].

and

While the plaintiffs have artfully pleaded allegations of corporate wrongdoing on the part of CanWest Global and its group of other corporations as federal companies, at bottom and in substance, those complaints are simply allegations of wrongful conduct by Broadcastings' Board or management such as (1) a failure to pay dividends, (2) a failure to involve Morton and Epstein in Broadcasting's management, (3) the application for the Victoria licence and, ultimately, (4) the Amalgamation in 2001 [at para 80].

[51] The motions judge concluded that since the lawsuit was about the internal management of Broadcasting, any questions about that management should be governed by the Manitoba Corporations Act in Manitoba by the Manitoba Court of Queen's Bench. He pointed out that only the Manitoba Court of Queen's Bench could give an oppression remedy under the Manitoba Corporations Act. He also reviewed the history of the relationship between the parties and found that their reasonable expectations were that any litigation about Broadcasting would be conducted in Manitoba in accordance with the law of that province.

[52] The motions judge concluded that the appellants could not obtain the remedies they seek under the CBCA. He held that s. 241 of that Act "cannot reasonably be construed to permit the prosecution of an oppression claim by a complainant in his capacity as a shareholder of a non-CBCA corporation brought in respect of the business and affairs of that non-CBCA corporation merely because that non-CBCA corporation happens to be affiliated with a CBCA corporation" [at para. 123].

[53] If the availability of the s. 241 remedy was before the motions judge and if he was correct in his conclusion that the remedy was not available to these appellants then his conclusion on convenient forum is unassailable. In fact, if he is correct, it is not a question of choosing the forum with the closest connection to the action and the parties, since only Manitoba is the appropriate forum. My concern with the motion judge's approach is that the availability of the s. 241 remedy was probably not before him. In effect, it seems to me that the motions judge turned the jurisdiction/convenient forum motion into a motion under Rule 20 for summary judgment or under Rule 21 to strike out the statement of claim as disclosing no reasonable cause of action.

[54] The appellants do not seek an oppression remedy under the Manitoba Corporations Act. They seek remedies under the CBCA. In my view, the appellants are entitled to have the jurisdiction and convenient forum issues determined on that basis. The motions judge may be right in his interpretation of the Manitoba and federal legislation, in which case the appellants' action will fail, but it seems to me that is a question to be determined at another time either under a Rule 20 or 21[3] motion or at trial. The merits of the claim should not, in my view, be decided at this preliminary stage.

[55] That is not to say that the motions judge's characterization of the nature of this action is immaterial. To the contrary, I accept that this lawsuit is about the internal management of Broadcasting. There is really no other way to read the amended statement of claim. It is all about how Mr. Asper and his corporations used their control of Broadcasting's board of directors and management to oppress the appellants as minority shareholders. The appellants allege, however, that in so managing Broadcasting the various CBCA corporations have violated that Act. Further, the appellants allege that many of those violations took place in Ontario. The case ought to be approached on that basis.

[56] The appellants submit that they are entitled to a remedy under the CBCA on the following theory. Section 241(2) provides that on an application by a "complainant", if the court is satisfied that "in respect of a corporation or any of its affiliates" that (for example) any act or omission of the corporation or any of its affiliates effects a result that is oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to or unfairly disregards the interests of any security holder or director, the court may make an order to rectify the matters complained of. "Corporation" is defined in s. 2(1) of the Act to mean a body corporate incorporated or continued under the CBCA and would thus include CanWest Global and Global Television. "Affiliate" is defined to mean an affiliated body corporate, and "body corporate" is defined to include a company or other body corporate "wherever or however incorporated" and thus need not be a CBCA corporation. Under s. 2(2)(a) one body corporate is affiliated with another body corporate if one of them is the subsidiary of the other or both are subsidiaries of the same body corporate or each of them is controlled by the same person. "Complainant" is defined in s. 238 to mean "a registered holder or beneficial owner, and a former registered holder or beneficial owner, of a security of a corporation or any of its affiliates" or "a director or an officer or a former director or officer of a corporation or any of its affiliates".

[57] Thus, prior to the amalgamation, the appellants qualified as complainants, being registered holders or beneficial owners of the securities of Broadcasting and directors of Broadcasting, an affiliate of CanWest Global. They say that a court could find that in respect of Broadcasting (an affiliate of Global Television) the acts of CanWest Global and its affiliates such as Global Television, CanVideo and the other defendants effected a result that was oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to the interests "of any security holder" or "director". A frailty in the argument is that the appellants must argue that "any" security holder or director includes a security holder or director of an affiliate that is not a CBCA corporation, in this case, Broadcasting. Case law under the Ontario Business Corporations Act tends to be against this proposition but, as the appellants point out, the OBCA is worded differently. See PMSM Investments Ltd. v. Bureau (1995), 25 O.R. (3d) 586 (Ont. Ct. (Gen. Div.))[4]. In any event, as I have said, it is my view that the court should not decide the merits of the claim for the purposes of determining jurisdiction or convenient forum. I will therefore apply the convenient forum test, taking the appellants' claim at face value.

[58] The starting place for considering convenient forum is "whether there clearly is a more appropriate jurisdiction than the domestic forum chosen by the plaintiff in which the case should be tried" (Frymer at p. 79). Also see Spar Aerospace Ltd. v. American Mobile Satellite Corp., 2002 SCC 78 at para. 69 and 70 and Amchem Products Inc. v. British Columbia (Workers' Compensation Board), [1993] 1 S.C.R. 897 at 921.

[59] The convenient forum test is discretionary and thus the motions judge's decision is entitled to considerable deference. However, in this case for the reasons that I have set out it is my view that the motions judge erred in principle by resolving the merits of the claim. In my view, he also misapprehended certain facts. For example, he found that this lawsuit "is nothing more nor less than an extension of the prior action of the 1980s on another battlefield". I do not think that is an entirely accurate characterization. The 1989 decision of Morse J. resolved the issues concerning Ventures and Global Television. The question of the management of Broadcasting was not an issue in that lawsuit. Broadcasting is mentioned in the reasons of Morse J., but as background to the litigation. Further, many of the complaints made by the appellants about Asper's running of Broadcasting echo complaints made by Asper about the way that Epstein and Morton ran Global Television. However, this present litigation is not simply an extension of the earlier Manitoba litigation.

[60] The motions judge also failed to take into account the many allegations in the statement of claim concerning the role of CanWest Television Inc. (CTI), which was a wholly owned subsidiary of Broadcasting and a CBCA corporation with its registered office in Ontario. CTI holds the television licences of the Broadcasting television stations. Many of the appellants' complaints concern agreements between CTI and Global or CanWest companies that unfairly impact on Broadcasting and that are governed by Ontario law.

[61] I will now turn to the factors to be considered under the convenient forum test. The cases identify a number of factors. See Muscutt at para. 41; Amchem Products Inc.; Eastern Power Ltd. v. Azienda Comunale Energia & Ambiente (2000), 178 D.L.R. (4th) 409 (Ont. C.A.); SDI Simulation Group Inc. v. Chameleon Technologies Inc. (1994), 34 C.P.C. (3d) 346 (Ont. Ct. (Gen. Div.)) and Spar Aerospace Ltd. at para. 71. In Eastern Power Ltd. at paras. 19 and 20, MacPherson J.A. identified the following factors:

(a) the location where the contract in dispute was signed,

(b) the applicable law of the contract,

(c) the location in which the majority of witnesses reside,

(d) the location of key witnesses,

(e) the location where the bulk of the evidence will come from,

(f) the jurisdiction in which the factual matters arose,

(g) the residence or place of business of the parties, and

(h) loss of juridical advantage.

[62] Taking into consideration that this case is not simply about contracts, I would apply the above framework for analysis to the convenient forum issue.

(a) The location of the dispute.

[63] The respondents say that this dispute is over the internal management of Broadcasting and that most of the decisions in issue were made in Manitoba. The motions judge adopted that position and went so far as to characterize the statement of claim as "legal casuistry [that] does not successfully camouflage the real nature of the action". I think this is too narrow a view of the dispute and in particular fails to credit the appellants' allegations concerning CTI, the holder of the television licences, whose registered office is in Ontario. It also fails to take into account that the appellants' allegations concern the impact of decisions involving Global Television, which is also centred in Ontario. On the other hand, it is fair to point out, as does the motions judge, that this case concerns revenue from television stations that are all located in Manitoba and the western provinces and do not carry on business in Ontario. On balance, this factor favours Manitoba as the appropriate forum, but I would not attach the same overwhelming weight to this factor that the motions judge did. In my view, he erred in principle by failing to take into account the significance of CTI and the contracts with CTI that are important elements of the dispute.

(b) The applicable law.

[64] The motions judge noted that the law governing the conduct of Broadcasting's affairs is that of Manitoba and that Manitoba law governs the amalgamation agreement. Because of the view he took about the merits of the claim, he attached no weight to the fact that the appellants alleged violations of the CBCA. In my view, since the appellants, rightly or wrongly, have chosen to sue for a remedy under the CBCA, it is that law and not the Manitoba Corporations Act that is the applicable law. The motions judge also failed to take into account that the contracts about which the appellants complain were made in Ontario and would be construed in accordance with the laws of Ontario. The fact that the appellants have sought a remedy under the federal statute favours neither Ontario nor Manitoba. Since the court would be required to apply the laws of Manitoba and Ontario, depending on the agreement, this factor would seem to be neutral, or at best, slightly favour Ontario because more of the relevant agreements were made in Ontario.

(c) The location in which the majority of witnesses reside.

[65] The motions judge found that any harm allegedly suffered by Broadcasting occurred in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia, where it owns and operates its television stations. He noted that the appellants claimed to have suffered damages in Ontario through diminution in the value of their shareholdings, although the legal situs of those shares is Manitoba. He concluded that the substantial majority of potential witnesses would seem to be in Winnipeg "at the true seat of power and through the chain of Broadcasting stations in the west." I would not quarrel with this conclusion, except that I would attach little weight to possible witnesses from the television stations. There is nothing in the material that would indicate that local management would have any relevant evidence to give. That said, this factor favours Manitoba as the place of trial.

(d) The location of key witnesses.

[66] The key witnesses are Asper, Morton and Epstein and the senior management of Broadcasting, CTI and CanWest Global. These witnesses are found in Ontario and Manitoba. This factor is neutral.

(e) The location where the bulk of the evidence will come from.

[67] The motions judge found that the "substantial majority of relevant documents seem to be located in Winnipeg and Western Canada". The appellants forcefully attack this finding, which they say is not founded on the record. I have examined the statement of claim and the affidavits that were filed before the motions judge. Respectfully, I must agree with the appellants. The books and records of Broadcasting and CanWest Global may be located in Manitoba. However, the books and records of the appellants, of CTI and Global Television are in Ontario. This factor is, in my view, neutral.

(f) The jurisdiction in which the factual matters arose.

[68] The factual matters arose in Manitoba and involve the internal management of Broadcasting. Over the years some Broadcasting board meetings have been held in Toronto, but most of the board meetings have been held in Manitoba. CanWest Global and Mr. Asper, the appellants allege, were instrumental in the oppression, are also located in Manitoba and many of the acts complained arose from decisions made in Manitoba. The amalgamation was effected in Manitoba. The various agreements that were the instruments used by the appellants to carry out the oppression were made and largely executed in Ontario. On balance, this factor favours Manitoba.

(g) The residence or place of business of the parties.

[69] The residence and place of business of the four appellants is Ontario. Mr. Asper resides in Manitoba. CanWest Global's registered office is in Manitoba but it carries on business in Ontario. Global Television's registered office is in Ontario. CanWest Global Broadcasting Inc.'s registered office is in Quebec. The registered office of Global Communications Limited is in Ontario. This factor favours Ontario.

(h) Juridical advantage.

[70] Juridical advantage is not said to be an issue in this case.

Conclusion on Convenient Forum

[71] Of the eight factors, three are neutral, three favour Manitoba, and two favour Ontario, one only slightly. However, determining convenient forum is not merely an exercise in mathematics. For example, the majority of witnesses would appear to come from Manitoba or the West, while most of the parties are in Ontario. But neither factor is of overwhelming significance in this case given the sophistication of the parties and the financial resources available to them. See Fidelity Management & Research Co. v. Gulf Canada Resources Ltd. (1995), 25 O.R. (3d) 548 (Ont. Ct. (Gen. Div.)) at 558.

[72] It would seem to me that looking at all the factors, they slightly favour Manitoba as the more convenient forum. But is that enough to displace the plaintiffs' right to choose the forum? While the burden was on the defendants to show that Manitoba was "clearly" a more convenient forum, as held in Frymer at p. 79, the "choice of the appropriate forum is designed to ensure that the action is tried in the jurisdiction that has the closest connection with the action and the parties". The underlying principle is, as La Forest J. said in Morguard at p. 1098, rooted in "reasons of justice, necessity and convenience" or as he said in Hunt at p. 326, "the discretion not to exercise jurisdiction must ultimately be guided by the requirements of order and fairness, not a mechanical counting of contacts or connections". Viewed in this way, Manitoba is clearly the more convenient forum. The factors concerning the location of the dispute and the jurisdiction in which the factual matters arose, which both favour Manitoba, are considerably more important than factors such as location of the parties. After all the counting of contacts and connections is done, this case is about the dissatisfaction of minority shareholders with the way they were and are treated by two companies based in Manitoba. One company, Broadcasting, is a Manitoba corporation governed by the Manitoba Corporations Act. The other, CanWest Global, although a federal corporation carrying on business throughout Canada, is resident in Manitoba. Reasons of justice, necessity and convenience not to mention the requirements of order and fairness call for this matter to be sorted out by the Manitoba Court of Queen's Bench.

[73] Accordingly, while I have found certain errors by the motions judge, I am of the view that he came to the correct conclusion concerning the convenient forum.

[74] In view of that conclusion, it is unnecessary to decide whether the motions judge was right to set aside service on Mr. Asper.

DISPOSITION

[75] Accordingly, since the motions judge properly stayed the proceedings on the basis that Manitoba is the convenient forum I would dismiss the appeal with costs on a partial indemnity basis.

[76] Following the hearing of the appeal, counsel for the parties exchanged bills of costs and then provided written submissions to the court. The appellants do not quarrel with the amount sought by the respondents and in fact had they been successful would have sought even higher costs. This was a complex matter and entailed considerable preparation by counsel on both sides. There was a vast amount of material involved. I can see no reason for substantially departing from the amount claimed by the respondents, except that I do not think the appellants should be required to pay the costs of three counsel on the appeal. Accordingly, I would fix the costs of the appeal payable by the appellants to the respondents at $56,200 inclusive of disbursements and G.S.T.

Signed: "M. Rosenberg J.A."

"I agree Austin J.A."

"I agree E.E. Gillese J.A."

RELEASED: "A.Mac.A" FEBRUARY 24, 2003

APPENDIX "A"

APPENDIX "B"

47. At the same time as CanWest Global's executives were retained to provide exclusive management services to Broadcasting, CanWest Global was also the exclusive provider of management services to its wholly-owned subsidiary, Global Television. With the systematic elimination of Epstein and Morton and independent senior management of Broadcasting, CanWest Global thus became the sole directing mind not only of its own interests and those of its wholly-owned subsidiaries but also of Broadcasting's interests.

…

51. As an example, over the protests of Epstein and Morton, the CanWest Global and Global Television nominees to Broadcasting's board of directors have continuously refused to permit Broadcasting to apply for any of the lucrative CRTC speciality channel licences. Asper, CanWest Global and Global Television have determined that speciality channel licences would be sought through CanWest Global or one of its subsidiaries and that Broadcasting and its subsidiaries would be excluded from the profits and other benefits of such licences.

52. The business plan of exploiting the benefits of speciality channel licences through CanWest Global or one of its subsidiaries without regard to the interests of Broadcasting had the effect of oppressing, unfairly prejudicing or unfairly disregarding the interests of Broadcasting's minority shareholders. The exploitation of these business opportunities through CanWest Global or other of its affiliates has resulted in all profits and other benefits therefrom being directed exclusively to CanWest Global. Since CanWest Global's management continues to act as the sole directing mind of Broadcasting, Broadcasting is powerless to act independently to advance or protect its own interests.

53. Broadcasting has also paid, over the protests of Epstein and Morton, ever-increasing fees for the services of CanWest Global's management. The majority of Broadcasting's board of directors appointed by CanWest Global has approved on an ongoing basis the non-arm's length contracts for the provision of management services by CanWest Global, without any consideration, or without any proper consideration, of the needs of the Broadcasting stations for any of these services or of the value of these services provided by CanWest Global or any of its affiliates. Such non-arm's length services include the following: management, programming, sales, corporate, legal, regulatory, financial, human resources, marketing, management information, promotions, graphics, media relations, administration, news, traffic, operations and engineering.

…

63. As confirmed by Asper's letter to Epstein and Morton dated December 20, 1990, written in Asper's capacity as Broadcasting's Chairman of the Board, CanWest Global agreed that Epstein and Morton would be permitted to question any program cost allocation arrangements directed by CanWest Global if these arrangements were not considered scrupulously fair or equitable to Broadcasting and its subsidiaries.

64. The arrangements remained in place until 1995 when CanWest Global's management unilaterally imposed a further revised method for allocating programming costs to each of the Global Television and Broadcasting stations. In the 1995 formula, CanWest Global's management proposed an allocation of programming costs, net of recoveries for outside third party sales, to each of the stations based upon the net air time revenue per station.

65. CanWest Global's management proposed this revision to the cost allocation arrangements in circumstances where

the net air time revenue for the Broadcasting stations had increased. In purpose and effect, the change was imposed to increase the proportionate amount payable by the Broadcasting stations in relation to the amounts payable by the Global Television stations. With the change in formula, Broadcasting's portion of programming costs increased from approximately 19% to over 25% of the total costs of national programming rights.

…

80. The new formula for programming charges imposed by CanWest Global's management required Broadcasting or its subsidiaries to pay for programming based on a formula that was later described in the Programming Services Agreement as the portion that (i) the acquisition costs of the programming that the English speaking population of the provinces where any Broadcasting station holds CRTC licence rights, is to (ii) the English speaking populations of the provinces where all Global Television and Broadcasting stations hold CRTC licence rights.

…

95. By correspondence dated November 24, 1997 to Peter Viner, the President and CEO of CanWest Global, Epstein protested the significant increase in programming costs charged to Broadcasting by its majority shareholder, particularly in light of the fact that the promised independent review of the sharing of programming costs between Broadcasting and Global Television had not yet taken place. Epstein protested the unilateral actions of the majority shareholder of Broadcasting in its apparent disregard of the July 14, 1997 commitment made by CanWest Global to abide by the decision of an independent valuator selected by Epstein and Morton.

96. Over the protests of Epstein and Morton, CanWest Global's nominees to the board of directors of Broadcasting later selected KPMG to review and evaluate the program charges already being paid by CTI to Global Broadcasting.

The actual retainer of KPMG did not take place for a year or more after CanWest Global's management unilaterally adjusted the program cost allocation formula and significantly increased the cost of program charges paid by Broadcasting stations effective September 1, 1997.

…

100. Under the arrangements unilaterally imposed by CanWest Global, Broadcasting was foreclosed from the possibility of acquiring programs on a more favourable basis relative to its own needs and circumstances. At the same time, the compulsory sharing of all programming acquired provided significant benefits to Global Television by allowing it to compete with and outbid other competitors in acquiring national programming rights. This access to the finances of Broadcasting has been and continues to be a critical factor in CanWest Global's and Global Television's growth and expansion in their existing markets and through acquisitions.

…

108. In purpose and effect, the related party transactions made directly or indirectly between CanWest Global and Broadcasting have brought about a corresponding reduction in CanWest Global's programming costs and a resultant increase in its profits. By permitting these increases in the cost of the related party transactions, CanWest Global's management failed in its fiduciary obligations to manage the business or affairs of Broadcasting in Broadcasting's best interests and in the best interests of all of its security holders.

109. Throughout the history of the dealings between Broadcasting and CanWest Global -- Broadcasting largely carries on business for all intents and purposes through related party transactions made with CanWest Global -- the nominees of CanWest Global to Broadcasting's board of directors did not disclose in writing their conflicts of interest or refrain from voting on the resolutions approving the numerous related party transactions with CanWest Global and

its other affiliates. Rather, the CanWest Global nominees to Broadcasting's board of directors have used their majority position to approve each of these non-arm's length contracts.

…

112. In circumstances where the common management of CanWest Global, Global Television and Broadcasting had a choice to favour the interests of CanWest Global and Global Television or the interests of Broadcasting, it always acted in the interests of CanWest Global and Global Television and to the detriment of Broadcasting.

…

124. Over the objections of Epstein and Morton, the CanWest Global management decided to prevent Broadcasting from using any Global programming or station identification if it sought and obtained a CRTC licence to operate a television station in Alberta. CanWest Global's management and its nominee directors to Broadcasting's board of directors thus subordinated the interests of Broadcasting, IBL, Epstein and Morton to the interests of CanWest Global and Global Television. They also permitted Broadcasting's majority shareholder to divert business or corporate opportunities from Broadcasting to itself or one or more of its affiliates. By engaging in such conduct, for which Asper, CanWest Global and Global Television are in law responsible, the nominee directors failed in their duties to act honestly and in good faith with a view to the best interests of Broadcasting or failed to exercise the care, diligence and skill that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in comparable circumstances.

…

142. In purpose and effect, CanWest Global is continuing to pursue a business plan that advances the interests of the stations operated through its wholly-owned subsidiary,

Global Television, in preference to the interests of Broadcasting's stations. By failing to maintain an even hand in considering the interests of these affiliated corporations under their common control, CanWest Global has breached its duty of good faith in the performance of its contractual obligations and breached its contractual commitments to manage Broadcasting in the best interests of all of its stakeholders. By causing CanWest Global to act in this manner, Asper has breached the fiduciary duties owed to his partners, Epstein and Morton, in respect of the business or affairs of Broadcasting and has acted in a manner that has oppressed, unfairly prejudiced or unfairly disregarded their interests within the meaning of section 248 of the CBCA.

…

149. Epstein, Morton, IBL and MAE have sustained significant losses or damages as a result of the conduct of the defendants set out in this claim. CanWest Global and its other affiliates have also been unjustly enriched as the result of their oppressive conduct, breach of fiduciary duties, misappropriation of Broadcasting's corporate opportunities, diversion of Broadcasting's profits and the other acts of misconduct set out in this claim. In addition to their claim for damages, the plaintiffs ask this Honourable Court to direct an accounting and payment of all profits to the plaintiffs made by Asper, CanWest Global, Global Television or other of their affiliates that are profits that should have been realized by Broadcasting.

…

150. Provided that Broadcasting remains under the exclusive management and control of CanWest Global, there is no reasonable prospect that the business or affairs of Broadcasting will be conducted in a manner that recognizes and deals fairly with the interests of Epstein, Morton and IBL in their capacities as directors, officers and minority shareholders of CanWest Global's affiliate, Broadcasting. It is just and equitable that this Honourable Court direct CanWest Global to purchase the Broadcasting shareholdings of the

plaintiffs at such price and under such terms as are determined [by] this Honourable Court after proper adjustments and payment by CanWest Global for such matters as are hereinbefore pleaded.

…

151. On April 13, 2001, CanWest Global announced in a press release that Broadcasting's most valuable asset, CKVU-TV (Vancouver), had been sold to CHUM Limited for approximately $125 million in cash. The plaintiffs first learned about this sale by means of this press release.

…

155. CanWest Global effectively appropriated to itself and transferred to its station CHAN-TV the goodwill and much of the value properly attributable to CKVU-TV. This is an act of oppression and CanWest Global is liable in damages to IBL and Epstein.

156. In response to the delivery of this Claim, CanWest Global and Asper caused Broadcasting to amalgamate with a newly-formed CanWest Global subsidiary, CanWest Broadcasting (2001) Ltd. and to force IBL and Epstein to become shareholders of CanWest Global.

…

161. On March 26, 2001, Broadcasting's board of directors held a meeting pursuant to CanWest Global's requisition. At this director's meeting, Epstein and Morton stated that they opposed the amalgamation. They voted against the resolution authorizing the amalgamation. But, the directors of Broadcasting, other than Morton and Epstein, followed CanWest Global's and Asper's directions and voted to approve the amalgamation, subject to shareholder approval.

…

170. In completing the amalgamation, CanWest Global has unfairly advanced its own interests as the controlling shareholder of Broadcasting in preference to the minority interests of IBL and Epstein. By eliminating the shareholdings of IBL and Epstein in Broadcasting, CanWest Global, and its affiliates and Asper continue to act in a manner that oppresses, unfairly prejudices or unfairly disregards the interests of IBL and Epstein within the meaning of section 248 of the CBCA.

[Emphasis added].

[1] Global Television has several wholly-owned subsidiaries that operate the Global Television Network. These subsidiaries are also federal corporations.

[2] I should not be taken as accepting that such a remedy is available in law, a matter I discuss below. Only that if such a remedy is available, Ontario courts would recognize a similar judgment made in other provinces.

[3] As was done in PMSM Investments Ltd. v. Bureau (1995), 25 O.R. (3d) 586 (Ont. Ct. (Gen. Div.)).

[4] In Moriarty v. Slater(1989), 67 O.R. (2d) 758 (H.C.J.) White J. gave an interpretation of the OBCA that favours the appellants' position. Farley J. in PMSM Investments at p. 595 notes that Austin J. in granting leave to appeal that decision wrote, "In my view there is reason to doubt the correctness of his decision. The plaintiffs are not security holders of the corporation within the meaning of those words as used in s. 247(2) of the O.B.C.A. At least that is how it appears to me." The case settled before the appeal was heard.