COURT OF APPEAL FOR ONTARIO

CITATION: McClatchie v. Rideau Lakes (Township), 2015 ONCA 233

DATE: 20150409

DOCKET: C58477

Doherty, Rouleau and Watt JJ.A.

BETWEEN

David McClatchie and Victoria McClatchie

Plaintiffs (Respondents/

Appellants by way of cross-appeal)

and

The Corporation of the Township of Rideau Lakes, and

Allen Churchill by his Litigation Guardian Alma Churchill

and Alma Churchill

Defendant (Appellant/

Respondent by way of cross-appeal)

Joseph Y. Obagi, for the appellant/respondent by way of cross-appeal

Robert J. De Toni, for the respondents/appellants by way of cross-appeal

Heard: January 6, 2015

On appeal from the judgment of Justice Paul B. Kane of the Superior Court of Justice, dated February 5, 2014, with reasons reported at 2014 ONSC 811.

Rouleau J.A.:

A. Overview

[1] In 2001, the respondents, David and Victoria McClatchie, bought Lot 16, a residential lakefront lot on the southern shore of Rideau Lake in eastern Ontario. Lot 16 is one of a series of lakefront properties created by subdivision plan 198 (“Plan 198”) from a portion of Lot 20, Concession 5, Township of South Elmsley, now Township of Rideau Lakes (“Lot 20-5”). Plan 198 also created a 40-foot road allowance running between the balance of Lot 20-5 and most of the lakefront properties, giving them access to a municipal road. However, no road has been built on the road allowance. Instead, the McClatchies and prior owners of Lot 16 have used a gravel road that cuts across Lot 20-5 for access. Lot 20-5 and the road allowance are owned by the appellant, Allen Churchill.

[2] This appeal relates to the McClatchies’ thus-far successful adverse possession claim over an L-shaped portion of the road allowance bordering Lot 16, as well as an easement of necessity the trial judge found existed over the gravel road on Lot 20-5 that the McClatchies use for access. Mr. Churchill argues that the trial judge erred in finding the McClatchies had demonstrated the required ten-year period of adverse possession over the L-shaped portion of the road allowance. Specifically, the trial judge erred both in interpreting the documentary proof tendered at trial and in failing to consider whether adverse possession had been demonstrated over every part of the land claimed. In Mr. Churchill’s submission, the documents, properly interpreted, show that the ten-year period had been interrupted. Further, the evidence of adverse possession over certain parts of the L-shaped portion was weak or non-existent. Mr. Churchill also appeals the finding of an easement of necessity over the gravel road cutting across his property. For such an easement, necessity is assessed at the time the lot is created. He says that when Lot 16 was created by Plan 198 in 1922, the road allowance created by the same plan provided access, precluding an easement of necessity.

[3] For the reasons that follow, I would allow the appeal in part. The trial judge’s conclusion that the McClatchies own the L-shaped portion of the road allowance by way of adverse possession was reasonable and supported by the evidence. This conclusion stands. But the trial judge’s other conclusion – that an easement of necessity existed over the gravel road on Lot 20-5 – was incorrect in law and should be set aside. It is not necessary to address the McClatchies’ cross-appeal, which asks this court to remit part of the matter back to the trial judge to determine whether the gravel road is an “access road” under the Road Access Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. R.34. I would declare it to be an “access road” under that statute.

B. Facts

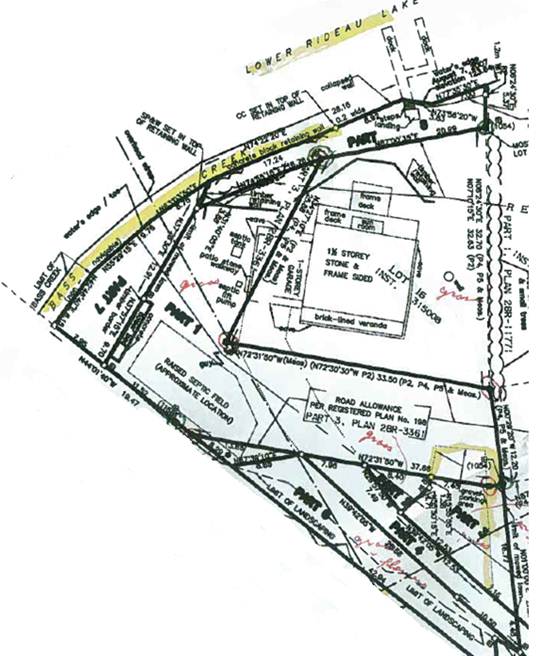

[4] In 1922, Plan 198 subdivided part of Lot 20-5 into 38 waterfront lots, one of which is Lot 16. Plan 198 also created a 40-foot road allowance running along the southern boundary of 23 of these lots. The portion of the road allowance that touches Lot 16 is L-shaped, as it forms the western and southern boundary of the lot: the road allowance starts just west of Lot 16, on the shore of Rideau Lake, then runs south along Lot 16’s west side, then turns east at Lot 16’s southwest corner, and then continues along the south side of Lots 17 to 38, ending at the highway between Concessions 4 and 5. The other two boundaries of Lot 16 are the lake to the north and Lot 17 to the east. In an appendix to this judgment, I have included a portion of a plan prepared by a surveyor, Mr. Riddell, that depicts Lot 16 and this road allowance.

[5] The L-shaped portion of the 40-foot road allowance on the west and south sides of Lot 16 is described as Part 1 of the Riddell plan. This L-shaped portion is the subject of the adverse possession appeal, and I will refer to it as Part R-1.

[6] Lot 16’s current owners, the McClatchies, purchased the lot in 2001 from Deborah Banford, who had previously owned it together with her now ex-husband, John Banford. Lot 20-5’s current owner, Mr. Churchill, acquired the property in the 1980s.[1] Since that time, he has entered into written agreements with the various lakefront lot owners, permitting narrow use of his lands for an annual fee. Three such agreements between him and Lot 16’s owners were tendered into evidence. At trial, it was an agreed fact that Mr. Churchill owned the 40-foot road allowance. It was also conceded that the McClatchies had a right-of-way over the road allowance, notwithstanding that this right-of-way had not been deeded to them.[2]

[7] The evidence established that the McClatchies and their predecessors in title have used Part R-1 in various ways. They have used portions of this space as a driveway and for a lawn or grassy area. The McClatchies built a concrete flower bed on one section of Part R-1. The house, garage and septic field for Lot 16 were built by the Banfords in 1983. The house is built entirely on Lot 16, but a part of the garage encroaches on Part R-1. The septic system, consisting of a septic tank, septic pump and raised septic field, is located on Part R-1. In fact, the septic field encroaches slightly beyond Part R-1 onto Lot 20-5.

[8] The evidence also established that, rather than using the 40-foot road allowance for access to the county road, the owners of Lots 16 to 38 have historically used several gravel roads that run across Lot 20-5. Since at least 1980, the owners of Lot 16 have accessed their property using primarily a gravel road that cuts across Lot 20-5 and connects their property to the municipal road. This gravel road is described as Parts 4 and 5 of the Riddell plan (the portion of the plan included in the appendix shows only Part 4). I will refer to them as Parts R-4 and R-5.

C. The law of adverse possession

[9] Before turning to the trial judge’s decision and the issues raised by the appellant, I will briefly review the law of adverse possession. This law is not in dispute. To establish adverse possession of certain lands, a claimant must demonstrate that throughout the ten-year adverse possession period, he or she: a) had actual possession of the lands in question; b) had the intention of excluding the true owner from possession; and c) effectively excluded the true owner from possession: Masidon Investments Ltd. v. Ham (1984), 45 O.R. (2d) 563 (C.A.), at p. 567.

[10] An adverse possession claim will fail unless the claimant meets each of the three criteria, and time will begin to run against the true owner of the lands only from the last date when all three are satisfied: Masidon, at p. 567.

[11] To establish actual possession, the acts of possession must be “open, notorious, peaceful, adverse, exclusive, actual and continuous”: Teis v. Ancaster (Town) (1997), 35 O.R. (3d) 216 (C.A.), at p. 221. If any one of these elements is missing at any time during the statutory ten-year period, the claim for possessory title will fail: Teis, at p. 221.

[12] If the claimant acknowledges the right of the true owner, then possession will not be adverse. Acknowledgment of title will thus stop the clock from running: Teis, at p. 221; Goode v. Hudon (2005), 30 R.P.R. (4th) 202 (Ont. S.C.), at para. 184; 1043 Bloor Inc. v. 1714104 Ontario Inc., 2013 ONCA 91, 114 O.R. (3d) 241, at para. 73.[3] Legislation likewise makes this clear. Section 13 of the Real Property Limitations Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. L.15, provides that a written and signed acknowledgment of title to land resets the clock for an adverse possession claim over that land.

[13] An agreement regarding one part of a property that the parties do not contemplate as applying to another part will not constitute an acknowledgement sufficient to interrupt adverse possession on that latter part: Tasker v. Badgerow, 2007 CanLII 23362 4086 (Ont. S.C.), at paras. 47-49, aff’d on other grounds 2008 ONCA 202.

D. THE DECISION AT TRIAL

[14] The trial judge granted the McClatchies ownership of Part R-1 by adverse possession pursuant to ss. 4 and 15 of the Real Property Limitations Act. He also found an easement of necessity over Parts R-4 and R-5.

(1) The adverse possession claim

[15] The apparent geographical boundaries of Lot 16 are larger than its legal boundaries. The testimony of several witnesses and various photos of the property taken over the years led the trial judge to make a factual finding that various tree lines, fences, and hedgerows created the impression that Lot 16 included parts of Lot 20-5. Specifically, Lot 16 appeared to include the L-shaped Part R-1. Based in part on this evidence, the trial judge found that the McClatchies and their predecessors in title, the Banfords, had mistakenly believed they owned Part R-1.

[16] Lot 16 and the properties surrounding it, including Part R-1, were converted to the Land Titles system on December 22, 2008. The trial judge correctly determined that as a result, any claim for adverse possession had to be made out before this date. Pursuant to s. 51 of the Land Titles Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. L.5, no claim by adverse possession or prescription can be brought based on facts occurring after that conversion date.

[17] The trial judge reviewed the evidence of Lot 16’s visual boundaries and the various ways its owners had used Part R-1 over the years. He then concluded that the evidence established that the McClatchies’ and Banfords’ possession of Part R-1 for the ten-year period preceding its conversion to Land Titles – that is, from 1998 to 2008 – was open, notorious, constant, continuous, peaceful and exclusive. The trial judge also concluded that their joint ten years of possession satisfied the “inconsistent use” requirement for adverse possession by knowing trespassers. The McClatchies had therefore proved adverse possession.[4] The trial judge went on to find, in the alternative, that the inconsistent use requirement was not applicable because there was a mutual mistake as to ownership of Part R-1.

(2) The agreements between the Churchills and the owners of Lot 16

[18] The Churchills and the owners of Lot 16 entered into three written agreements from 1988 to 2002. According to Mr. Churchill, these agreements interrupted the running of any adverse possession claims. The trial judge disagreed. The agreements and their relevant parts are as follows:

1. An agreement signed by the Banfords in October 1988, stating as follows:

This is an agreement whereby Allen and Helen Churchill, owners of the road allowance and land immediately to the south and west of Lot 16, shown on registered Plan 198 in the Township of South Elmsley, and owned by John and Debbie Banford, give permission to John and Debbie Banford to use said road allowance for casual and incidental purposes (access, parking, lawn), for the sum of one dollar annually.

2. An agreement dated September 1998 and signed by Mrs. Banford, then the sole owner of Lot 16, providing as follows:

This is an agreement whereby Allen and Helen Churchill, owners of land immediately to the west and south of lot 16, shown on registered plan 198, part of lot 20, in the township of South Elmsley, within the new township of Rideau Lakes, Ontario, and owned by Debbie Banford, give permission to Debbie Banford to use said Churchill land for the purposes of access, parking, and lawn (but not for buildings, fences, etc[.]), for the sum of one dollar annually. This permit may be terminated by either party upon one month’s notice.

3. An agreement signed by the McClatchies in June 2002, providing as follows:

This is an agreement whereby Allen D. and Helen Churchill, owners of the land immediately to the south of the public road allowance running adjacent to the south side of Lot 16, shown on registered plan no. 198, Lot 20, Concession 5 of the geographic Township of Rideau Lakes in the Province of Ontario, do hereby give permission to David and Victoria McClatchie, owners of Lot 16, to use said Churchill land, that part shown roughly as a triangle on the survey plan, drawing #99034J02.DWG, of John Goltz, surveyor, for the purposes of travel, parking, and lawn (but not for erecting buildings or fences, or laying asphalt, etc[.]), and this for the sum of $100.00 annually. This permit may be terminated by either party upon one month’s notice.

[19] The Banfords paid the annual $1 fee each year from 1988 to 2001. The McClatchies paid the $100 fee only in 2002 and refused to pay after that.

[20] The trial judge highlighted several features of these agreements. One such feature was that there was a change in their wording, both as to what the Churchills owned and what the owners of Lot 16 had permission to use. The 1988 document states that the Churchills are owners of “the road allowance and land immediately to the south and west of Lot 16” and allows the Banfords to use the “said road allowance”. The 1998 document states that the Churchills are owners of “land immediately to the west and south of lot 16” without mention of the road allowance. It purports to allow the Banfords to use the “said Churchill land” rather than allowing use of the road allowance. The 2002 document is quite different. It states that the Churchills are owners of “land immediately to the south of the public road allowance running adjacent to the south side of Lot 16” and it allows the McClatchies to use “said Churchill land”.

[21] The trial judge found that the absence of a specific reference to the road allowance in the 1998 agreement was intentional, the reference having been dropped from the 1988 version. The absence of a reference to the road allowance reflected the belief, then held by both the Churchills and Banfords, that the township owned the road allowance. Therefore, the 1998 agreement did not purport to cover the Banfords’ use of Part R-1; it was not an acknowledgment of Mr. Churchill’s title to Part R-1 and so did not interrupt the running of the adverse possession claim over it. Rather, the 1998 document marked the beginning of the running of the adverse possession claim.

[22] As I will explain, the central issue on appeal is whether the trial judge erred in his interpretation of the 1998 document.

[23] The trial judge’s finding that, in 1998, the Churchills did not believe they owned Part R-1 also provided part of the basis for the trial judge’s alternative finding that there was a mutual mistake as to the ownership of Part R-1.

(3) The exchange of letters between counsel

[24] Mr. Churchill also argues on appeal that an exchange of letters between his counsel and counsel for the McClatchies broke the chain of adverse possession. The first letter was sent by counsel for the McClatchies in April 2004, in the hope of regularizing the status of the road allowance. Counsel for Mr. Churchill responded in September 2007 on a “without prejudice” basis. The trial judge found that these were exploratory settlement offers and hence privileged. The trial judge further found that even if the letters were not privileged, they did not contain any acknowledgment of Mr. Churchill’s title sufficient to interrupt the running of the prescription period.

(4) Access to Lot 16

[25] As mentioned, no road has ever been built on the 40-foot road allowance created by Plan 198. At trial, no evidence was led regarding how Lot 16 was accessed prior to 1980. The evidence as to access to Lot 16 from 1980 to 2008 was that the gravel road over Parts R-4 and R-5 was used and that, on occasion, Mr. Banford had used an alternate road to access his lot, a road that ran partly over the road allowance.

[26] The trial judge found that the 40-foot road allowance could never have been used to access Lot 16 in part because a rock bluff along the road allowance prevented any passage at that point. He also found that parts of the road allowance distant from Lots 16 had been sold by the Churchills, which made it impossible for the owners of Lot 16 to use the road allowance to access their property. Additionally, he noted that the conveyances of Lot 16 and other lots adjacent to the road allowance included rights-of-way over internal roads on Lot 20-5. He reasoned that these rights-of-way would not have been necessary if the road allowance actually provided access to these lots. Also, Mr. Churchill repeatedly admitted on examination for discovery that the gravel road over Parts R-4 and R-5 provided the only access to Lot 16.

[27] As a result, the trial judge concluded that an easement of necessity was created over Parts R-4 and R-5.

E. Issues on appeal

[28] The issues raised on appeal are as follows:

1. Did the trial judge err in finding that the McClatchies and Banfords had extended their use and occupation over the whole of Part R-1?

2. Did the trial judge err in finding that the period of adverse possession had not been interrupted by the September 1998 agreement or the September 2007 letter sent by Mr. Churchill’s lawyer?

3. Did the trial judge err in finding an easement of necessity over Parts R-4 and R‑5?

4. If the trial judge did err in finding an easement of necessity, should the McClatchies’ cross-appeal be granted so that the trial judge can determine whether Parts R-4 and R-5 constitute an access road under the Road Access Act?

F. analysis

(1) Did the Banfords and McClatchies exercise exclusive use and occupation over all of Part R-1?

[29] Mr. Churchill submits that while the McClatchies may have exercised possession over all of Part R-1, the evidence was clear that their predecessors in title had not. Specifically, Mr. Churchill argues as follows:

1. The evidence of Mrs. Banford did not establish that she had maintained the easterly or grassy portion of Part R-1, nor was it clear that she had ever maintained the westerly portion of Part R-1 beyond the area around the septic tank;

2. The evidence of Mrs. McClatchie confirmed that the property was not being maintained for a year or two prior to the McClatchies’ viewing of the property in 2001;

3. The location of the septic field was not apparent and obvious so as to constitute an open and notorious use; and

4. The trial judge erred in using the construction of a concrete flower bed by the McClatchies as justification for adverse possession of a portion of Part R-1, because it was built well into the ten-year adverse possession period.

[30] I would not give effect to these submissions. All of the trial judge’s findings are supported by the evidence led at trial and provide a solid basis for his conclusion that the whole of Part R-1 was occupied and used to the exclusion of the Churchills.

[31] The trial judge found, at para. 55, that a line of trees and hedges were “visual indicators … [that] led Mr. and Mrs. McClatchie to believe that what they were buying included … R-1”. He also found, at para. 57, that “[t]he Banfords and the McClatchies mistakenly believed they were buying a lot with a distinctive visual outline. Both couples indicated Mr. Churchill did not use what they understood to be the land they thought they had purchased, including R-1.”

[32] The trial judge explained as follows, at para. 56:

[T]hroughout their ownership, the Banfords and the McClatchies openly occupied and used Part R-1. They cleared snow as required over their driveway. They maintained the lawns and flower beds on this land. Mr. McClatchie constructed a concrete flower bed on the southwest portion of R-1. The raised septic field, septic and septic tank cover on Part R-1 are apparent and obvious to anyone. They appear to be part of the land associated with this home.

[33] In addition, the trial judge found confirmation for the evidence of the Banfords and McClatchies in the photographs that were tendered in evidence. These photographs clearly suggested that Part R-1 was part of Lot 16.

[34] After setting out the uses that the Banfords and McClatchies had made of Part R-1, the trial judge went on to find, at para. 59, that “the nature, extent and presence of these elements, together with the location of the overhang of the garage, prevented any other use by Mr. Churchill and constituted obvious, continuous possession by the dominant owner of Lot 16”.

[35] Absent palpable and overriding error, these findings of fact are owed deference. The trial judge was in the best position to assess the evidence, including the evidence tendered by Mrs. McClatchie and Mrs. Banford as to the maintenance of the property. The trial judge did not, as suggested by Mr. Churchill, rely on the construction of the flower bed to establish adverse possession. Rather, the construction of the flower bed by the McClatchies was simply one of many indicators that the owners of Lot 16 believed this property included all of Part R-1 and acted in a manner consistent with this belief.

[36] In assessing the evidence of the various witnesses, the trial judge had the benefit of seeing the witnesses point to various parts of the plan and photographs referred to and entered in evidence. This advantage simply reinforces the importance of the deference that is owed to the trial judge on his findings of fact.

(2) Did the September 1998 agreement or the September 2007 letter interrupt the period of adverse possession?

[37] The interpretation of the September 1998 agreement between the Churchills and Mrs. Banford, as sole owner of Lot 16, is the main issue on appeal. Specifically, the issue is whether the reference in 1998 to “land immediately to the west and south of lot 16” owned by the Churchills was understood by the signatories to include the road allowance. The trial judge determined it was not.

[38] Mr. Churchill argues that the trial judge erred in his interpretation of the 1998 agreement. He maintains that the agreement is clear and unambiguous. It is an acknowledgement that the Churchills own the land “immediately to the west and south of lot 16”. Any confusion that may have existed at the time as to whether the Churchills or the township owned the road allowance was eliminated prior to trial. By the date of trial, it was clear that Mr. Churchill owned the road allowance, including Part R-1; the September 1998 agreement should be read consistent with this fact. The 1998 agreement constitutes, therefore, an acknowledgment by Mrs. Banford of the Churchills’ title to all of the land to the south and west of Lot 16, including Part R-1.

[39] I would not give effect to this submission. Agreements are not interpreted in a vacuum. As explained in Sattva Capital Corp. v. Creston Moly Corp., 2014 SCC 53, [2014] 2 S.C.R. 633, at para. 47, the overriding concern in interpreting contracts is to determine the parties’ intent and the scope of their understanding. To do so, a judge must read the contract as a whole and give the words used their ordinary and grammatical meaning, consistent with the surrounding circumstances known to the parties at the time of the contract’s formation. The 1988 and 2002 documents provide some context and are of assistance in interpreting the words used in the 1998 document.

[40] The issue the trial judge had to resolve in this case was what the parties to the agreement understood to be the land that the Churchills owned. In other words, did the parties, when they entered into the 1998 agreement, believe that the Churchills owned Part R-1, the road allowance, and that the Churchills were granting permission to Mrs. Banford to use it as well as Lot 20-5? Or, did the parties believe the township owned Part R-1?

[41] If the former were true, the running of the adverse possession claim would be interrupted from the time the 1998 document was signed until 2001, when the McClatchies purchased the property. In other words, the claim would fail. But if the latter were true, the acknowledgement would not cover Part R-1. In that latter case, the 1998 agreement should be read as giving Mrs. Banford permission to use parts of Lot 20-5, including Parts R-4 and R-5, to access her property, but as having no application to Part R-1. This is what the trial judge found.

[42] In interpreting the 1998 agreement, the trial judge correctly read it and interpreted its terms in context, taking into account the document as a whole as well as the relevant background and circumstances. He applied the principles of contractual interpretation to the words of the written contract, considered in the light of the factual matrix. As explained in Sattva, this is a question of mixed fact and law, and the standard of review of the trial judge’s findings is thus palpable and overriding error, unless the appellant can point to an extricable error of law: Sattva, at paras. 50-55.

[43] As discussed, the trial judge interpreted the words “land immediately to the west and south of lot 16” in the 1998 agreement as referring to the lands immediately to the west and south of the road allowance. He concluded that, when the 1998 agreement was entered into, the Churchills’ understanding of who owned the road allowance had changed from their belief in 1988 that they owned the road allowance. By 1998, the Churchills had come to believe that the township owned the road allowance. This finding by the trial judge is supported by the evidence tendered at trial. Support for the finding that the Churchills’ belief regarding ownership of the road allowance had changed includes the following:

1. During Mr. Churchill’s testimony, as read in from his discovery transcript, he stated that “this whole [ownership] thing was in flux for a while because we weren’t sure what that road allowance up there consisted of or who it was owned by.” He did not know whether he was equally uncertain about these matters when he purchased Lot 20-5 in 1980;

2. The 1988 agreement stated that the Churchills owned the road allowance;

3. During Mr. Churchill’s testimony, as read in from his discovery transcript, he said he got the Banfords to sign the 1988 agreement “because the question of the ownership of the total road allowance over here, the 40-foot road allowance, was being talked about and people were building on it. And the question was: Did it belong to the municipality or did it belong to the buyers or did it belong to [the owner of Lot 20-5]?”;

4. Mr. McClatchie testified that Mr. Churchill had described the road allowance in November 2001 as a “municipal road allowance”;

5. The 2002 agreement referred to the Churchills as being the owners of the land “immediately to the south of the public road allowance running adjacent to the south side of Lot 16”;

6. In Churchill v. Irvine (23 May 2007), Perth, 3085/96 (Ont. S.C.), a May 23, 2007, trial decision in a claim Mr. Churchill had brought against the owners of Lot 18 on Plan 198, Pedlar J. noted in his reasons that “[t]hrough extensive investigation and research between the parties and various lawyers for the Municipality, it has been agreed that the Municipality owns … the 40-foot road allowance”; and

7. In a summary judgment motion brought by the township earlier in this proceeding, in which the township denied owning the road allowance, Mr. Churchill did not take the position that he owned the road allowance. He took no position and left ownership to be determined by the court. The motion judge concluded that the township did not own the road allowance and dismissed the McClatchies’ adverse possession action against it.

[44] From the foregoing, it is clear that in 1988 Mr. Churchill believed he owned the road allowance, and that sometime between 1988 and 2002 he came to believe he did not own the road allowance. Precisely when that belief changed is a factual issue. The trial judge’s finding that it had changed prior to or at the time of the signing of the 1998 agreement finds support on the record and is owed deference. After considering all of the evidence, the trial judge drew the following conclusion, at paras. 89, 91, and 124-25:

Mr. Churchill, knowing the importance of obtaining written acknowledgement of his title in order to defeat adverse possession and his experience in preparing and getting these contracts signed, must in preparing [the 1998 document] have dropped his previous reference to the Road Allowance because of his recognition or belief, as later acknowledged before Pedlar J., and contained a similar contract he later obtained from [the McClatchies], that the Road Allowance was owned by the Township and not by himself.

…

What in fact was occurring was the evolution of Mr. Churchill’s knowledge over some 20 years in relation to the Road Allowance and his belief that the Township owned it. That is why the wording of these contracts begins in 1988, with the statement that he and his wife owned the Road Allowance, then to the deletion of that statement in 1998 contract and then finally the open admission in the 2002 contract that his ownership begins to the south of the Road Allowance.

…

Mr. Churchill has a Phd. and was well versed in the issues regarding his lands and the waterfront owners. He did not simply forget to include reference to the Road Allowance in [the 1998 document]. ...

[Mr. Churchill] has now twice in two actions appeared in court and taken the position that he does not own the Road Allowance or he took no ownership position as to it. These factors combined with the ambiguity indicated above in [the 1998 document] must be read against his drafting of such document and leads me to conclude that Mr. Churchill had given up any claim of ownership to the Road Allowance by September 14, 1998.

[45] Although one could reach a different conclusion on the record, I am unable to say that the trial judge’s finding of fact is palpably wrong.

[46] As to the September 2007 letter sent by Mr. Churchill’s lawyer, that letter is directed to the issue of the prescriptive easement over Parts R-4 and R-5. It was written shortly after Pedlar J.’s judgment in Irvine, where it is stated that the road allowance, Part R-1, was owned by the township. As a result, I agree with the McClatchies that the letter was not intended to protest the McClatchies’ use of Part R-1.

(3) Did an easement of necessity exist over Parts R-4 and R-5?

[47] At trial, the McClatchies abandoned any claim for an easement by prescription over Parts R-4 and R-5. The only claims they advanced with respect to Parts R-4 and R-5 were an easement of necessity and equitable proprietary estoppel. The claim for equitable proprietary estoppel was rejected by the trial judge, and that finding is not challenged on appeal. The trial judge did, however, find an easement of necessity. The appellant submits the trial judge erred in so doing.

[48] Easements of necessity are easements presumed to have been granted when the land that is sold is inaccessible except by passing over adjoining land retained by the grantor. The concept arises from the premise that the easement is an implied grant allowing the purchaser to access the purchased lot. See Nelson v. 1153696 Alberta Ltd., 2011 ABCA 203, 46 Alta. L.R. (5th) 113, at paras. 40-43, leave to appeal to S.C.C. refused, [2011] S.C.C.A. No. 423; and Dobson v. Tulloch (1994), 17 O.R. (3d) 533 (C.J. (Gen. Div.)), aff’d (1997), 33 O.R. (3d) 800 (C.A.).

[49] Necessity is assessed at the time of the original grant: Nelson, at para. 42; Dobson, at p. 541. In the present case, it is obvious from the 1922 subdivision plan, Plan 198, that access to Lot 16 was to be along the 40-foot wide road allowance the plan created. Although the deed to Lot 16 does not contain mention of a right-of-way along the road allowance, Mr. Churchill has conceded that the McClatchies have this right.

[50] The trial judge rejected the argument that an easement of necessity did not arise because access to Lot 16 was assured at the outset by Plan 198’s creation of the 40-foot road allowance. He found that the road allowance never provided access to Lot 16 because a rock bluff located on the road allowance prevented passage at that point. As discussed, he found support for this conclusion in various other facts, including Mr. Churchill’s admissions on discovery and his creation of rights-of-way over Lot 20-5 to access some of the lakefront lots along this same stretch of the 40-foot road allowance. Finally, the trial judge concluded that necessity was established because Mr. Churchill no longer owned parts of the road allowance. This prevented owners of Lot 16 from having a right to pass over the full length of the allowance to access the public road.

[51] Mr. Churchill submits that the trial judge’s findings reflect a misunderstanding of the law and a misapprehension of the evidence. I agree.

[52] Whether Mr. Churchill decided to create rights-of-way over his property is irrelevant to the issue of whether necessity existed at the time of the original grant. It is clear that in 1922, the road allowance gave the owner of Lot 16 a legal route, if not an actual route, to access the property. By including a road allowance in Plan 198, the grantors made sure that Lot 16 was not landlocked in the legal sense of the term, thereby avoiding the creation of an easement of necessity.

[53] The fact that the owners of Lots 16 to 38 have long preferred to drive over Lot 20-5 and may have found it quicker and more convenient than navigating the road allowance does not prove necessity in 1922. One of the prerequisites for an easement of necessity is that it must be necessary to use or access the property; if access without it is merely inconvenient, the easement will not be implied: Nelson, at para. 38.

[54] On appeal, the McClatchies argue that although Lot 16 was created by Plan 198 in 1922, it may not have been in fact sold until 1954. As a result, they submit that necessity should be assessed as of that later date. I would not give effect to that submission because, even if the McClatchies are correct, it does not change the outcome. The McClatchies bear the onus of proving necessity, but they led no evidence suggesting that anything had changed between the registration of the plan in 1922 and 1954.

[55] With respect to the trial judge’s finding that necessity was established because of a rock bluff preventing passage over the road allowance, I agree with Mr. Churchill’s submission that no evidence was led at trial establishing that the rock bluff was located on the road allowance. The McClatchies’ own surveyor testified that he did not know where the rock bluff was located in relation to the road allowance. Moreover, he testified that he suspected the bluff had resulted from excavation and was not natural; this implies it may not have existed in 1922 or 1954.

[56] In my view, the trial judge also erred in relying on the fact that Mr. Churchill no longer owned parts of the road allowance to prove necessity. As explained, necessity is assessed at the time of the grant. Subsequent sales of sections of the road allowance have no impact on this assessment. Further, it was not the McClatchies’ position that using the road allowance to access their lot was impossible because Mr. Churchill no longer owned parts of it. Mr. Churchill’s ownership of the road allowance was an admitted fact and, as a result, evidence of ownership of the road allowance was not an issue at trial. The trial judge ought not to have disregarded the admission of the parties and made findings contrary to these admitted facts.

(4) Should the trial judge determine whether Parts R-4 and R-5 are an access road?

[57] With respect to the McClatchies’ cross-appeal, Mr. Churchill concedes that the gravel road, Parts R-4 and R-5, constitutes an “access road” under the Road Access Act. Since the road meets the definition of an “access road” under s. 1 of that statute, I would declare it to be an access road. Therefore, I do not need to deal with the cross-appeal.

G. DISPOSITION

[58] As a result, I would allow the appeal with respect to the finding of an easement of necessity and set aside the trial judge’s order on this issue. I would dismiss Mr. Churchill’s appeal in all other respects. I would also declare Parts R‑4 and R-5 to be an access road under the Road Access Act.

[59] If the parties are unable to agree on costs, I would ask the appellant to submit brief written submissions not exceeding three pages in length within 15 days of the release of this decision, and the respondents to provide their response within 15 days thereafter, also not exceeding three pages in length.

Released: April 9, 2015

(DD) “Paul Rouleau J.A.”

“I agree Doherty J.A.”

“I agree David Watt J.A.”

Appendix A: Lot 16 as shown on the Riddell plan